Malpractices at the bridge table take watching to detect , says S.Ananthanarayanan.

Some games are contests of motor skills and there are others that rely on strategy. Games like cricket, football or tennis do have elements of strategy, but they are mainly contests of motor skill. Chess and some card games are different. These involve no motor skill, but they call for thinking and reasoning, to evaluate strategy, and overcome an opponent’s strategy.

The New York Times reports a case in the world of competitive bridge, where there are allegations of cheating against a team that has notched up an impressive record of wins. In motor sports, circumstances that give a participant an advantage is easily detected. But what could be a form of malpractice in contests that are said to be of mental ability? The NYT story relates how a strategy of ‘separating signal from noise’ and statistical analysis could follow up on the allegations.

In the world of chess, there have been instances where players in world championships took the help, while playing, of advisers, or even computers. When such a thing happens, or is suspected, we are dealing with a gross violation, of the player being assisted during the game by a physically separate entity. But what could be a case of cheating in bridge?

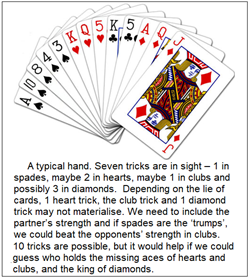

Bridge is a game where a pack of cards is dealt to four players, in two teams, and there is a sequence of play of a card by each player, according to the rules of the game. The specific cards that are played, each time, decide which side wins that play, and the game is to see whether a side, which won the contract to score a certain number of wins, succeeds or fails. The complexity arises from the contract having to be auctioned and won with each player having seen only her own cards, and then, for most of the game, half the cards staying concealed (the partner of the player who wins the contract opens out her hand once the opponents play the first card).

Each play of cards by the four player is called a ‘trick’ and with 52 cards in the pack, there are 13 of these. Each player bids, for her side to win the greater part of the tricks, and the contract goes to the highest bidder when rounds of bidding stop. The process of bidding is itself a means to communicate the strength of the bidder’s hand –and the bidding convention used by a team is formally conveyed to the opposite side. And again, during the play, the cards a player chooses to throw down, when tricks are won or lost, are legitimate means, known equally to the opponents, to convey or conceal information.

Cheating in bridge would be when a player communicates information by other methods. This could be by physical indications, like a twitch, a hand gesture, facial gesture, and so on. Or it could be by an undisclosed convention of bidding or play. The first kind could be prevented by physical blinds that separate players. As for the second, this has to be detected when a side consistently does better, in uncertain situations, than was statistically possible within the rules– followed by analysis of the bids and cards led or discarded, to find correlation with the lie of cards.

Cheating at cards is obviously more common when the game is played for stakes of money. bridge is a game where a score is kept, and hence can be played for money. But there are other games, like Poker, or ‘Flash’ (the Indian, 3-card variety), blackjack or canasta, which are played almost always for money. In the James Bond novel, the character Goldfinger claims that he has a problem facing open spaces, and when playing in the lawn outside the hotel, chooses always to face the hotel. The opponent hence plays with his back to the hotel. When one such opponent was consistently losing money, James Bond reasoned that the secret lay in the position of the players, and discovered an accomplice in the hotel room, who viewed the opponent’s cards through a telescope, and passed hints to Goldfinger.

In games like poker or canasta, it is admittedly chance, or luck, that decides the winner. The skills of professionals hence lie in avoiding any show of emotion (the ‘poker face’) or in psychologically inducing the opponent to misread the value of cards, her own, or the ones that she cannot see. And as further aids, players could use trick methods of shuffling or dealing cards, marking the cards, and so on, to turn the odds in their favour.

Competitive bridge, in contrast, eliminates the value of the hand that a player has been dealt. In this method, the real opponents of a team are not the pair they are sitting with at the table, but another pair, at another table. The hands are dealt not at the time of playing, but in advance, by the organisers of the tourney. And a second set, of the same hands, is created for use at the second table. It is the pair at the other table, with the same hand, that each pair is playing against. And the objective is not to win more tricks than or to limit the tricks of the opponents at one’s own table, but to do better than other pair which has the same cards.

In this sense, the money incentive to beat chance and win does not feature in competitive bridge. The greater complexity of bridge, with no role of demeanour, psychology, etc., however, makes the field highly competitive, and there is prestige in being champions. There are also sponsors who incentivise teams, and there not a few instances of players resorting to different methods, to narrow the uncertainty of the lie of cards and hence the best line of play.

The New York Times story is about Fulvio Fantoni and Claudio Nunes, players from Italy, who had been ranked No. 1 and No. 2 by the World Bridge Federation. Now, bridge has an element of uncertainty and the players’ skill lies in finding the play for the highest probability of a win. The success of Fantoni and Nunes, however, appeared to be better than was possible with skill alone. For instance, when the bidding suggests that a particular player has high cards in a suit, the play with the higher probability of success is when this player is made to play her high card, or a low card, before others. But when a team is seen to play in the opposite way, and is seen to succeed, consistently, it looks like the team had extra information.

In 2014, the NYT story says, video recordings of the European Bridge Championships were publically uploaded. Maaijke Mevius, a physicist in the Netherlands, had heard reports about Fantoni and Nunes. She was not a bridge expert, but she thought her training as a scientist could help her notice features that expert analysts had missed. As video recordings capture a great many movements of the players, detecting the instants where information is being passed is challenging. But Mevius’ scientific work, which involved distinguishing ‘signal from noise’ in the lab setting, helped her classify the information that the video recordings contained. And her review brought it out that when Fantoni or Nunes played a card, they did not place the card on the table with the same orientation all the time, but there was a pattern. She shared this with Boye Brogeland, a Norwegian who had a record of detecting malpractice in bridge. A group of experts then got to work and with the help of statistical analysis, they discovered the code – that certain ways of placing the cards –for example, vertically or horizontally - passed information – whether the player had an honour card whose location was uncertain, for instance - which helped the partner make the correct play!

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Do respond to : response@simplescience.in-------------------------------------------