Ancient defense against invasion by the sea has been uncovered., says S.Ananthanarayanan.

Coastal cities are in danger because the sea level is set to rise through the rest of the century. It has become urgent that states find methods to cope, if not to relocate.

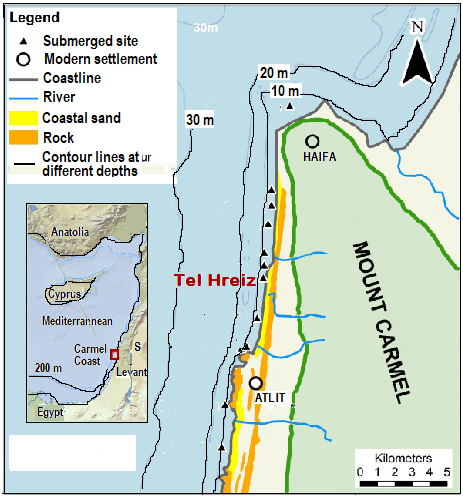

It would appear that people living along the Mediterranean coast made similar efforts as long as 7,000 years ago. Ehud Galili, Vered Eshed, John McCarthy and Liora Kolska Horwitz from the Universities of Haifa, the Hebrew University and the Israel Antiquities Authority, Jerusalem, Jonathan Benjamin from Flinder’s University of Adelaide, and Baruch Rosen, a researcher in Petah Tikva, Israel, describe, in the journal, PLOS ONE, new discoveries at the submerged Neolithic settlement of Tel Hreiz, off the Carmel coast, Northern Israel. Underwater archaeological investigations, the paper says, have revealed a 100 m long, boulder-built seawall, apparently to protect the settlement from sea level rise caused by melting glaciers, between 12,000 and 7,000 years ago.

During the Ice Ages, seawater was trapped in the form of ice, in glaciers, and this led to drop of sea levels. The last Ice Age peaked about 25,000 years ago. After the peak, there was melting and retreat of glaciers, which led to rising of sea levels. Ice Ages are believed to arise, and recede, due to cycles in the plane of the earth’s orbit around the sun. The current geological age, which has been consistently warm, and has supported the growth of civilization, is known as the Holocene (or recent) Age. The Holocene is considered an ‘inter-glacial’ age, i.e., before the next Ice Age, in some thousands of years.

Humans are known to have become the dominant species after the end of the last Ice Age. Continued good climate helped agriculture to develop, the creation of settlements and the beginnings of cities. The rising sea levels during the final stages of the melting of the glaciers, however, submerged some coastal habitation sites and there are numerous instances in different parts of the world. Tel Hreiz, in the Mediterranean, is one such, discovered by accident in 1960, when divers were looking for shipwrecks. Tools made of flint and human skeletons were found, but the site created no archeological interest.

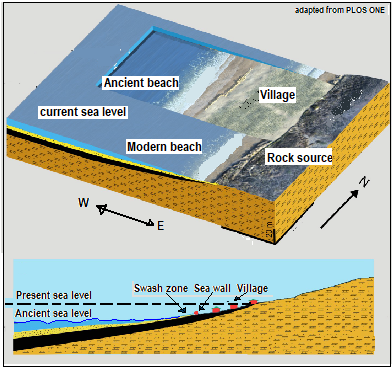

The changes in sea levels and the progress inland of the seacoast, since 9,000 years ago, has been well documented, the paper says. Over the first2,000 years, at the rate of 4mm a year, the sea level rose a whole 8m, and again by 8m over the next 3,000 years.

Studies of ancient sites submerged in the process show a pattern, that the older sites are found in deeper water and further into the sea, the paper says. The earliest site, some 9,000 years old, is 200-400m and 8-12m below the sea level. And there are fifteen other sites, which are less than 8,000 years old, less than 200m offshore and less than 5m under water, the paper says.

The sites were not systematically investigated, but human activity and sea storms accidentally washed aside the sand that had covered (and hence protected) the sites and exposed them to view. In the case of the Tel Hreiz site, natural processes have revealed archeological material extending from the current coastline to a depth of 4 m, the paper says. And a winter storm in 2012, and another in 2915, washed away more of the sand and revealed a formation of rocks, which raised questions of how the formation came about and what it was meant for.

As the action of waves causes erosion and would wear away the details of archeological remains, it is fortunate that these sites were protected by a layer of clay and sand, the paper says. While removal of this layer, for study, is laborious, archeologists make the best of events like storms that expose the features of interest. In the case of the rock formation at Tel Hreiz, the formation is partly visible during low tide, but the surf interferes with examination and study. Study was hence carried out by scuba divers while the rocks were submerged, during high tide, and the sea was calm. And it was important to carry out the study as fast as possible, before rocks corroded or other remains were moved about by currents.

The boulder-built, wall feature at Tel Hreiz is usually covered by 3m of sand, but they were uncovered during the storms of 2012 and 2015, which provided opportunities for study. During these studies, the exposed section of the wall was measured, drawn to scale and photographed, all features were documented and its precise location was noted. By aerial surveys of the modern beach, coastal ridge and immediate offshore area, the physical environment of the boulder-built feature was reconstructed, to help understand its function.

The underwater survey and the items salvaged, the paper says, disclose a thriving settlement, some 11,000 square meters in area. The finds include structures like a building, huts, tools and implements made of flint, human skeletons, possible burial places, remains of domestic and hunted animals, marine and fresh-water fish and olive pits, which suggest oil extraction. The appearance is of a single, sedentary community, engaged, like others in the region, in agriculture, raising animals and fishing. And based on Carbon Dating, that it lasted 300-500 years.

Now, coming to the boulder-built wall structure, this consists of sections in a straight line, extending to more than 100m, on the eastern, seaward side of Tel Hreiz. It is about 3m below the water, some 90m offshore and parallel to the coast. The southern end is buried in the sand and may continue for a considerable distance. From the arrangement, nature and size of the stones, it is evident that “the boulder-built feature is a continuous and unified architectural entity which forms a wall,” the paper says.

The stones are mostly large boulders, 200 to 1,000kg in weight, naturally rounded and not cut of quarried, and appear to have been transported from sources at some distance. This indicates that it was by a well-organized community that the wall had been built. It also appears that at the seaward side of the wall was a swash zone, a beach area alternately covered and exposed by waves. If this was the case, it is unlikely that the wall was a field boundary or a place for keeping animals. As there are structures that may have been dwelling to the east of the wall, it does appear that the wall was meant to protect and separate the settlement from the open sea.

The structure seems clearly to be a wall constructed by the community for protection, against what would have been seen, over generations, as an advance of the seafront towards the village. The structure may have been effective only for some time, as it was submerged, and there is evidence to that show that Tel Hreiz later moved 50 to 200m to the east.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Do respond to : response@simplescience.in-------------------------------------------