The legendary nose of man’s best friend can do more things than smell, says S.Ananthanarayanan.

Dogs, with their agility, pack loyalty and trainability, have stood by humans through recorded history. They have tended sheep, drawn sleds, been watchdogs, accompanied the hunt and led the blind. But they are best known for the acuity of their sense of smell – they are trackers, they can find lost persons or lost objects and their noses can detect firearms or contraband in sealed baggage.

Anna Bálint, Attila Andics, Márta Gácsi, Anna Gábor, Kálmán czeibert, Chelsey M. Luce, Ádám Miklósi and Ronald H. H. Kröger, from Lund University, Sweden, Eötvös Loránd University, Hungary and the University of Bremen, Germany, write in the journal, Scientific Reports, that dog’s nose has yet another capability – it can detect heat from warm objects, like an infrared camera

While the dog’s eyesight is less specialized than our own, the dog’s nose, as an organ of smell, has adapted to more than ompensate. The insides of the canine nose consists of folds of skin, which contain 300 million smell-sensing nerve endings, compared to just 6 million that humans have. Like some other animals, the dog’s arsenal includes a special organ that detects trace chemicals, an ability that has disappeared in humans. The part of the dog’s brain that is used for smells is 40 times larger than the part that we use.

The dog also separates the actions of sniffing and breathing, so that it can pass air continuously over the olfactory organs without disturbing respiration. Further, each nostril acts independently, to detect smells from different directions. By putting together the smells that come to each nostril, the dog can ‘smell in 3 dimensions’, just like we can make out distance and depth with the help of our two eyes. Overall, the dog’s nose is considered 100,000 times more efficient at smelling than the human nose

A marked feature of the canine nose is that it is damp and cold. Being damp would be useful to capture chemicals that odours consist of. The feature of being cold, however, is not easy to understand, as lowering of temperature generally lowers nerve sensitivity. Except in the well-known case of the crotaline snake, which has cavities, the pit organs, which act like pinhole cameras, to focus infrared radiation from warm prey. These act as a kind of infrared eyes and help the animal hunt in complete darkness. The temperature of the pit organs, however, is kept low, with the help of a special arrangement to cause evaporative cooling.

The paper brings out that photons of the infrared radiation from objects, like prey animals, that are only moderately warm, are too feeble to activate the photo-pigments in the eye. An organ that could detect heat would hence depend on an arrangement to collect a good number of low energy, infrared photons and get warmed. That it would be important for such an organ to be colder than the emitter of the radiation to be detected is a reason to explain the feature of the pit organs being cooled. The paper also says that a sensitive area in the nasal passage of the vampire bat, which is able to detect the warm spot, and hence the blood vessel, on the body of an animal it attacks, is kept a little cooler than its surroundings.

The discussion of the heat sensing organs of species of snakes, insects and the bat being kept cool leads to the notion that the cold nose of the dog may also have a heat sensing function. “The closest wild relative of domestic dogs, the grey wolf, preys predominantly on large endothermic prey and the ability to detect the radiation from warm bodies would be advantageous for such predators,” the paper says.

To see if the domestic dog did have a heat sense, the authors of the paper carried out a series of experiments. The first series, at the Lund University, Sweden, was to see if the dogs could make out a heat signal at all. Three dogs were trained to respond with one of two choices, in the presence of absence of a weak heat signal. The source of the signals was a pair of identical panels, approximately one foot square. One face of the panels was 11-13°C warmer than the surroundings, while the other face was almost at the temperature of the surroundings. At each trial, one warm face and one cool face was presented to the dog. Just below each panel was a bowl of food. The bowl below the warm panel could be opened, by working a lever, but not the bowl below the cool panel.

The dogs were first trained to work the lever when they chose the bowl below one of the panels. At the start, the lever of the below the warm panel was partially worked, so that the dog could see the reward, and the trainer pointed to the warm panel. When the dogs had learnt the procedure, both bowls were fully closed and the trainer delayed pointing to the warm side, to allow the dogs to take in the heat signal from the panels.

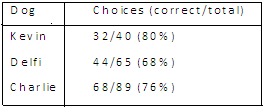

stimulus was reduced, by placing covers, with only a four-inch opening, before each panel. With a bit of help to get started, in case there had been a gap, there were several sessions of data collection, with 15 or less trials in each session. The results, as we can see in the table, show that that the dogs were able to make out the weak heat signal:

The next series of tests, conducted in Hungary, was to investigate the excitation of different parts of the brain when the dog was exposed to warm or neutral stimuli. Here again, a pair of warm or neutral surfaces was used, and displayed to the dogs that had been trained to lie motionless in the MRI scanner – the equipment that records activity of different parts of the brain.

The results, the paper says, were that the warm stimulus elicited a response in a specific area of the brain, the area that is associated with sensory information. The design of the experiment and elimination of signals other than the perception of heat, the paper says, and identifies the response in the brain as related to the nasal region. “The location of the detected activation is clearly distinguishable from the auditory and the olfactory cortical areas,” the paper says.

Just how the low heat that strikes the small, furless, nostrils of the dog is translated into nerve signals is still unclear, the paper says. In the case of pit organs of the crotaline snake, there is a cavity that concentrates radiation and a lightweight structure that is warmed. The dog’s nose, in contrast, has no cavities and the surface has only protuberances of nerve endings.

But the study shows that “sensing weak thermal radiation is within the abilities of the species Canis familiaris, or the domestic dog!

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Do respond to : response@simplescience.in-------------------------------------------