The early night owl was a dinosaur, says S.Ananthanarayanan.

Birds are essentially daylight creatures, but there are some that have adapted to hunt in the night. And night birds have evolved very acute visual and auditory sensitivity. As birds are known to have evolved from dinosaurs, a valid question is whether this ability to hunt in poor light existed among dinosaurs too.

Jonah N. Choiniere, James M. Neenan, Lars Schmitz, David P. Ford, Kimberley E.J. Chapelle, Amy M. Balanoff, Justin S. Sipla, Justin A. Georgi, Stig A. Walsh, Mark A. Norell, Xing Xu, James M. Clark, Roger B. J. Benson, from University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa, Universities of Oxford, Edinburgh and Iowa, John Hopkins University, Midwestern University, George Washington University, Claremont McKenna, Scripps, and Pitzer Colleges, Claremont and Institutes and Museums in Los Angeles, New York, Edinburgh and Beijing, answer the question in the affirmative. In their paper in the AAAS journal, Science, they identify a species of dinosaur, which lived in the Late Cretaceous epoch (100-66 million years ago), and had the same adaptation for poor light as the present night birds.

The ancestors of birds were a group of meat-eating dinosaurs called theropods, a bipedal group with hollow bones and three-toed feet. We usually associate dinosaurs with huge and fearsome creatures – and the largest dinosaurs belonged to the group of theropods. Theropods, however, were of all sizes, going down to less than a kilogram, and it is from this group that some evolved into birds.

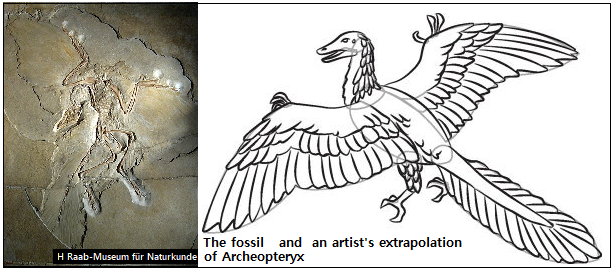

The Archaeopteryx, discovered in the 1860s, was a chicken-sized creature that had many features of dinosaurs, like jaws with sharp teeth, three fingers with claw and a long bony tail, but also had a pair of broad wings, that enabled it to glide or fly, as well as long, powerful front limbs. The Archaeopteryx was hence considered the transition, or the bridge, between reptiles and birds. More specimens of feathered dinosaurs, however, have been discovered, and there are now more candidates for the beginning of the evolutionary tree of birds

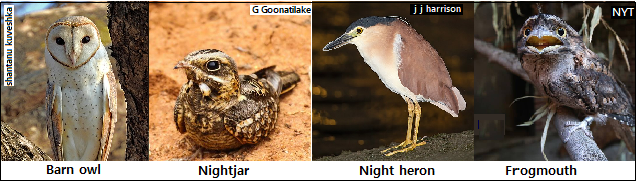

Birds have specialized, according to conditions, available prey or sources of food, and predators, and there are now some 10,000 different species. And as mentioned earlier, the majority are birds that hunt or forage in daylight. There are, however, a few species, mainly different kinds of owls, the nightjar, the frogmouth, the night heron, which have specialized for hunting in the dark or in low light.

The authors of the paper note that this adaptation is in the form of large pupils of the eyes, to increase sensitivity to light, and again in the features of the ear, to detect feeble sounds, a feature that is most marked in the barn owl, which can hunt in total darkness. These adaptations result in skeletal structure to accommodate the larger eyeball, in the case of vision, and the longer organ called the lagena, in birds, or the cochlea, in mammals, of the inner ear, that processes sound, in the case of hearing. “Most nocturnal birds have conspicuous modifications of the visual system, and specialized nocturnal foragers of active prey combine adaptations of both vision and hearing,” the paper says. However, although these features of the skeletal structure should be evident in fossils, whether and how night hunting in birds evolved from their dinosaur ancestors, or even the biology of dinosaurs, is not well understood, the paper says.

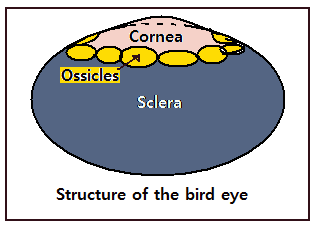

The authors of the paper hence undertook a survey of the dimensions of the eye cavity and the inner ear of nearly a hundred living birds and extinct dinosaurs, using fossil records, in the case of dinosaurs. In respect of vision, the anatomical feature studied was the scleral ossicle ring, or the bony casing as part of the sclera, the container, the outer layer of the eye, a feature seen in birds and in many vertebrates. And in respect of hearing, the cochlea, the spiral shaped, bony, resonating cavity, lined with sound-sensing filaments, to pick up different frequencies

The eyes of birds that hunt in low light are highly adapted to suit the purpose. Unlike the eyes of mammals, these eyes are not round but tubular, and packed with rods, as opposed to cones, for greater sensitivity. And they have no eyeball that can move – instead, the large vision apparatus is rigidly fixed to the bony, ossicle ring. The bird hence has to turn its head to change its gaze. The eyes, however, are larger, in the case of the owl, the eyes account for 3% of the body weight – a thousand times more than ours- and are hence highly adapted to see in great detail and in poor light.

As for hearing, study of 88 species of living birds, the paper says, shows that birds that hunt in the dark all have elongated or highly elongated cochlear ducts, as opposed to daytime birds. “This suggests that duct elongation is an adaptation for auditory foraging, contradicting the hypothesis that it evolved to facilitate intraspecific communication,” the paper says. Woodpeckers, which use sounds to track concealed insects, also show limited-moderate duct elongation, the paper says.

The question now is whether such adaptations for low light foraging can be seen among dinosaurs. The paper reports that adaptation to night hunting is there in a group of small dinosaurs that existed from the Jurassic, which is the epoch just before the Cretaceous (100-66 million years ago), and through the Cretaceous. Computer based reconstruction of the casing of the eyes show large eyes and openings, suggesting adaptation for night hunting in the case of two groups. The first, an early group, retains much of the general features and may not have specialized its manner of hunting. The other, called Shuvunia Deserti, which appears in the Late Cretaceous, has developed a bird-like skull and limbs and digits suited for scratching and digging.

The hearing apparatus was studied using micro-CT scans. Here, it is found that Shuvunia has an elongated cochlear duct, with large diameter and curved, similar to that of the current barn owl. While such hearing adaptation is seen in the therapods, the elongation is exceptional in the case of Shuvunia and one more, the paper says, in a manner comparable to how the elongation in the barn owl is not even seen in other owls.

The paper notes that acute hearing ability, while exceptional among birds and, is not so rare among dinosaurs and is fairly common among mammals that hunt at night. The paper surveys the occurrence of both visual and hearing acuity, other features, like modification of dental endowment and limbs suited for digging and scraping, to expand our understanding of ancient ecosystems and how specialization for hunting at night took place, independently among birds and mammals.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Do respond to : response@simplescience.in-------------------------------------------