Lovers of coffee would be alarmed to learn that their favourite bean in in danger, says S.Ananthanarayanan.

Even if the world contains global warming to 2°C, global vegetation would be far different from what it is. While there would be increase in tree cover in some places and drying up at others, specific crops may not survive the rise in temperature. And one such is the Arabica coffee bean.

Aaron P. Davis, Delphine Mieulet, Justin Moat, Daniel Sarmu and Jeremy Haggar, from Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and the University of Greenwich, in UK, DIADE (DIversity-Adaptation-plant DEvelopment) Institute in Montpellier, France and Welthungerhilfe, an independent, German NGO working in Freetown, Sierra Leone, however, have some good news. They write in the journal, Nature Plants, that there is a wild variety of coffee, which matches the current leading variety, and could do well in a warmer world.

There are two main strains of coffee that are cultivated. The most popular is Arabica and the second is Robusta. Arabica is known for its fine flavour and accounts for 60% of the coffee grown. The Arabica plant, however, is delicate and needs care to bring home the crop. Robusta is not as high in flavour, but it is a hardier plant, and accounts for nearly all the remaining 40%.

Arabica was grown at higher altitudes in Ethiopia, Africa, since several centuries. But the trade shifted to Yemen, and, from the port city, Mocha, the coffee travelled to all parts of the world. And as Yemen lies in the Arabian Peninsula, the variety got the name, Arabica. Arabica is a mild coffee, rich in natural sugars and fats, moderate on caffeine and can be brewed to have much sought-after nuances of flavour and aroma. The Arabs tried protectionism, but seeds or seedlings were soon smuggled out to other lands and the Dutch grew coffee in plantations in Ceylon, Sumatra and Java. Coffee is now grown in many places, Brazil and India being important centres, and, in value of international trade, coffee is the world’s largest agricultural product.

The coffee plant needs reasonable warmth, and plentiful rainfall. The ground should be well drained. Coffee is hence grown in the belt between 30°north and south of the equator, at places with hill slopes, for efficient drainage. Areas in Africa, South America and Asia were well suited and Arabica coffee was widely cultivated. The industry, however, hit a roadblock with the emergence of the Coffee Leaf Rust, a fungus that forms on the leaves. The fungus makes the leaves wither and the plant produces less berries and hence less coffee.

The answer was in a related variety, which could resist the fungus, and some other parasites too. The new variety was also hardier and could manage in less exacting conditions. Naturally, the variety is called Robusta, and it has become enormously popular. It has higher caffeine content, which is a reason for its resistance to pests, but it does not have the delicate flavour of Arabica. However, Robusta is cheaper and the two varieties are almost equally popular, with some who prefer Robusta, and there is a market for blends.

Enter, global warming

Rising global temperature, however, would now affect both coffee varieties. “Successful coffee farming occurs within a relatively narrow climatic envelope and is susceptible to weather perturbations throughout its growth and life cycle, rendering it sensitive to climate change,” the paper in Nature Plants says. It is considered that by the year 2050, half the acreage under coffee would become unusable for quality coffee.

The paper says that there are are three possible solutions. The first, to relocate cultivation, would mean finding land in places with better conditions, and over 100 million livelihoods would have to be managed. The second is to adapt farming practices, like irrigation, providing shade or covering the soil. This has some potential, but involves extra costs. And the third is to develop new, climate resistant varieties. Efforts in this direction are on, but are in the early stages, the paper says. There are some 120 other varieties that would be able to survive warmer and drier conditions, but none of them has the flavour or other attributes of Arabica and Robusta.

This is the context of the attention shifting to a wild variety, known as Coffea stenophylla, a variety found in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Ivory Coast, in West Africa. This, and other wild coffee varieties, which were studied and consumed in the later 1800s and early 1900s, had gone out of focus because of the overwhelming success of Arabica and Robusta. Stenophylla was a noted instance, the paper says, and cites 19th century publications which say the species had “excellent taste, as good as ‘best mocha’ and possibly superior to all other coffees, including Arabica.” But such references died out by the 1920s, the paper says, probably because there was no cultivation and the species was rare even in the wild.

In 2018, however, field work revealed that stenophylla was still there in the wild, in Sierra Leone, in West Africa. In 2020, the current authors hence obtained sample, stenophylla coffee beans. The samples were then brewed and evaluated by five professional panels, in a blind exercise, against a high-quality Arabica sample, from Ethiopia, a medium quality sample from Brazil and a high-quality Robusta sample from Indonesia.

The evaluation, across the five panels, and through detailed assessment of features and tasting notes, revealed that “stenophylla has a complex flavour profile, natural sweetness, medium–high acidity, fruitiness and good body, as in higher quality Arabica……. These results credibly corroborate historical reports,” the paper says.

But then, despite similarity in taste and aroma, the paper says, stenophylla differs widely from Arabica and Robusta - evolutionary history is not shared, the areas of occurrence are widely separated, and environmental requirements are different. The paper estimates the mean temperature that suits stenophylla as 25-26 °C against 19.0°C for Arabica. This is a margin of 6.8°C, and there is a comparable margin in respect of Robusta.

The finding, that the new variety thrives at a higher temperature, opens the doors to developing an alternative to Arabica and Robusta in the face of climate change. But this apart, the paper notes that specialising the strains of Arabica and Robusta had effectively reduced the diversity of coffee strains. Cross-breeding, for flavour gains, resulted in loss of resilience. But with stenophylla entering the list of available species, this aberration could be corrected, the paper says.

Indian coffee and Coffee Houses

It is said that a 16th century Sufi pilgrim smuggled coffee seeds from Mocha, and brought them to Chikmaglur, in the foothills of the Western Ghats. And since the 19th century, the potential for export led to vast area under coffee in the hilly parts of south India.

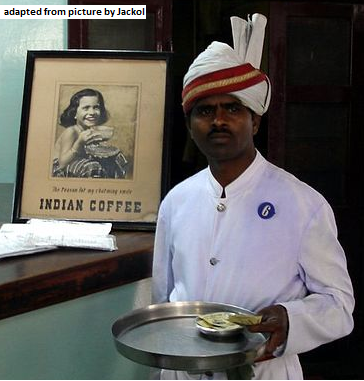

In 1942, the Coffee Board was set up to regulate coffee production. To popularise coffee outside the south India, the Board opened Coffee Houses in most cities in India. These became iconic centres, where aromatic coffee and quality snacks were served by turbaned waiters.

In 1957, it was considered that Coffee Houses had served their purpose and should be shut down. And the staff, mostly from Kerala, were offered a termination bonus. A delegation, led by A K Gopalan, the Marxist leader, however, met Pt Nehru and it was decided that instead of shutting down, each of the Coffee Houses would be offered to the staff working there, if they agreed to form an association. About half the Coffee Houses hence continued, under an umbrella Association of Coffee Houses.

In time, in the face of competition, most of these closed down, with the premises, which were at prime locations, fetching handsome returns. And only a handful of the original Coffee Houses are working now. Except in the city of Jabalpur, in Madhya Pradesh, which has eight outlets and houses the HQ of the Indian Coffee Workers' Co-operative Society.------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Do respond to : response@simplescience.in-------------------------------------------