It took a century for the earth to warm. Would it still take time to stop?, asks S. Ananthanarayanan.

Early last month, Mark Hertsgaard, director of the media support group, Covering Climate Now, and Laura Helmuth, editor-in-chief of Scientific American, interviewed Dr Michael E Mann, director of Penn State Earth System Science Center and Saleemul Huq, director of the International Centre for Climate Change and Development, in Dhaka. And the subject of the interview was a mention in the 6th Assessment Report of the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), issued in August 2021, that the global temperature would stabilise rapidly, as opposed to slowly, once the pace of greenhouse gas emission was controlled.

Hertsgaard started off with the note that all climate modelling, so far, has considered that CO2 in the atmosphere, once it builds up, persists, or stays there for decades, even centuries. Hence, even after the world manages to stop adding CO2 to the atmosphere, it has been understood that global warming would continue for 30-40 years. While there was limited progress after the COP21, Paris in 2015, and disappointment in COP26 at Glasgow in 2021, the idea that warming does not end when emissions are controlled has been another damper. And the feeling has spread that holding the warming to 1.5oC or even 2oC may not be possible.

Except, Hertsgaard said, that the IPCC report of August 2021, even before the Glasgow meet, had put forward a new understanding – that warming does not continue once emissions are controlled, but stabilises within three years. The trouble, however, is that this important information is tucked away, virtually buried, within the report. The whole repot is nearly 4,000 pages long and the technical summary is 159 pages. A technical person studying the report would very likely miss this information. Even the 24-page Summary for Policymakers follows the pattern of the reports, only omitting details, and is not a reader-friendly rendition of the report.

The journal, Scientific American, however, had spotted this nugget. And in Oct 2021, before the Glasgow meet, an article by Mark Fischetti, senior editor, said, “Climate models consistently show that “committed” (baked-in) warming does not happen. As soon as CO2 emissions stop rising, the atmospheric concentration of CO2 levels off and starts to slowly fall because the oceans, soils and vegetation keep absorbing CO2, as they always do.”

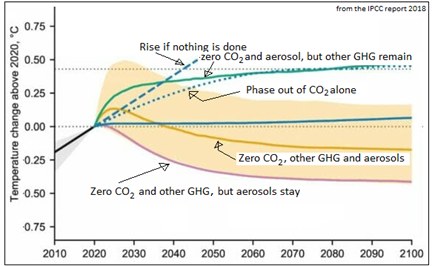

Michael Mann explained that the slowing down of warming is implicit in the idea of the carbon budget, that there is an extent of CO2 that we can still push into the atmosphere, before we hit 1.5oC of warming. If we speak of a budget, it means warming will stop if we stop emissions when the limit is reached, he said. But the reason we still thought warming would continue is because there is warming of the sea, a great heat sink, that also takes place, and the sea is slow to warm. But the understanding that has surfaced over the last decade is that there are other processes, that draw CO2 out of the atmosphere, that continue after we stop pumping CO2 into the atmosphere, and the CO2 content begins to drop.

However, this only applies to the surface temperature, not the temperature of the sea, which continues to absorb heat. Warming of the sea would hence continue, with effects like the melt of sea ice, and the sea-level would rise. The sea-level is now about a foot higher than at pre-industrial times, and would rise by another foot, even if we do contain CO2, by half within this decade, and completely by mid-century. But this we must, Mann said, “so that this foot does not become a metre!”

Hertsgaard came in to say that this science, that warming is going stop very soon after (and if) we arrest emissions, creates a paradigm shift - it psychologically encourages people, the young people who had the largest stakes, to believe that working to reduce carbon would positively benefit them. And thinking like this would affect politics, the kind of leaders we elect, and then government policy.

Saleemul Haq, from Bangla Desh, was introduced as the person who had trained diplomats from the global South, who had influenced insertion of the 1.5oC target into the Paris agreement of 2015. In Bangla Desh, Haq said, the effects of the current 1.1oC warming global warming were already part of daily life. His country had been dealing with extreme weather and increased flooding since a decade and common people had found ways to adapt to global warming, he said.

The affluent West was yet to understand, he said. During the Glasgow conference, countries most at risk had pressed for the outcome of the conference to be called the Glasgow Climate Emergency Pact. But the US, UK, affluent countries, watered it down to the Glasgow Climate Pact. But warming with catch up and they will understand, or their children will, Haq said.

Global warming was common understanding in Bangla Desh, Haq said, and a subject that the local press actively covered. The world’s press was present in strength during the inauguration and the start of COP26, when dignitaries were there, but they did not stay for the proceedings. It was the Bangla Desh TV channel that was there till the end, Haq said.

The reports of IPCC have been criticised, in the past, for being difficult to understand, if not unreadable. There was a defence that the Summary for Policymakers is the ‘most widely read’ part of the report. This really says nothing, and a glance at the summary would show that it is scarcely helpful even to a technical person. And we see that the part of the 2021 report that Scientific American considered the most important was missed by the world press, what to say of policymakers.

Hertsgaard observed that if the press reported the whole news, not just the gloomier parts, but also the information that taking steps could turn things around, there could be more attention to what is said.

Other pollutants

The other GHG we emit is methane, Michael Mann said. But methane is a gas that decomposes relatively quickly, unlike CO2, which sticks around for long periods. The methane that we emit is hence not all an addition that stays as a load in the atmosphere.

But there is another pollutant that acts the other way. This consits of the sulphate aerosols that arise from sulphur impurity in coal. Aerosols actually block or reflect some of the sunlight, an effect we call aerosol masking, which offsets a part of global warming. Now, when we stop burning coal, we do reduce CO2 emission, but we also lose out on a bit of global dimming that aerosols bring about.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Do respond to : response@simplescience.in-------------------------------------------